One Smile At A Time - Cleft Lip and Palate Repair

Parade Magazine, New York - Dec 15, 2002

Published at cleftAdvocate with permission of

Parade Magazine, the author and the photographer.

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner.

Further reproduction or distribution is prohibited without permission.

Copyright Parade Dec 15, 2002

| ||||

One Smile At A Time

Parade Magazine, New York; Dec 15, 2002

Copyright Parade Dec 15, 2002

By John Albert Casey

The expectant mom knew something must be wrong when the ultrasound technician abruptly got up in the middle of her sonogram and rushed out to get a doctor. "I felt shock, chills, when they told us," says Robin Sherak Taubman, 36, a lawyer who lives in New York City with her husband, Louis, 34, also a lawyer, and their 3-year-old son, James. "You have so many expectations when you're pregnant, but your child having a cleft lip is not one of them."

It turns out that cleft lip and palate deformities are the most common facial birth defects, occurring in about one in 700 live births, or in about 5000 children in the U.S. every year. As the Taubmans' sonogram showed, their baby, Eli---born last May---was healthy in every way, but he had a pronounced cleft in his upper lip. "It's tough, but it falls into perspective pretty quickly," his mother says. "Eli was beautiful. He just had a cosmetic problem."

In the past, fixing that problem would have required a series of surgeries---extending into adolescence--- putting the child at risk for lasting psychological damage. Fortunately for the Taubmans, not long after Eli's birth, they heard about Dr. Court Cutting of New York University Medical Center in Manhattan.

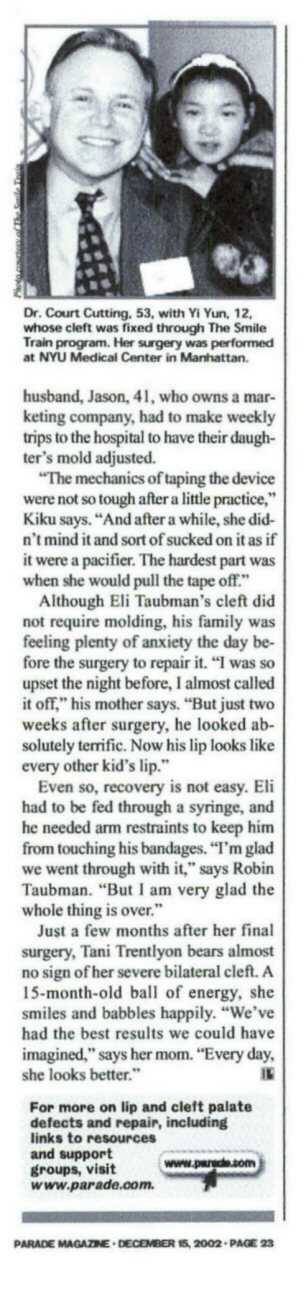

Dr. Cutting is one of the country's premier plastic surgeons specializing in lip and cleft palate procedures. Working with Dr. Barry Grayson, an orthodontist, Cutting pioneered a technique that has revolutionized the treatment of lip and palate defects.

"Twenty years ago, surgery was not done until the child was a teen," says Cutting, 53. "By then a lot of psychological damage is done. Now we get in before the child's first birthday."

The new technique--- nasal alveolar molding, which Cutting and Grayson developed over 18 years---means that just one operation is needed to repair the lip, nose and gums. (Those with more severe clefts need another operation at about age 1.) The children usually bear almost no trace of their former disfigurement.

If a cleft is going to form, it begins eight to 12 weeks into pregnancy, when the front of the face fuses together. "For some reason that we don't understand, the fusing is incomplete in some children," says Cutting. "It's actually the fetus' tongue working against this unfused tissue month after month that widens the cleft."

Nasal alveolar molding helps reshape the mouth, lip and nostrils before surgery, lessening the severity of the cleft. Surgery is performed two to six months after birth.

Parents work first with an orthodontist. A plastic mold of the infant's mouth, lip and nostrils is created. The infant wears the device around the clock for as long as six months, and the child's face grows into the mold's shape, reducing the cleft. Every week, the mold is reshaped to keep the facial features growing as they should be.

"The device restores so much of the face's shape," says Dr. Cutting. "It gives us much better results after surgery. And, at the end, the parents get this great payoff---that they helped their kid through this mess."

Dr. Dean Toriumi, president of the American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, agrees that molding can make an enormous difference. "It's an innovative technique," he says. "It can reduce the burden of surgery for these very young patients."

Still, months of wearing a molding device can be hard not only on the child but also on the parents. "Molding is for the determined parent," Cutting says. "It's not for the faint of heart."

Kiku Trentlyon's daughter, Tani, was born with a severe bilateral cleft lip and palate. "At times it was difficult," says Trentlyon, 31, a sports trainer in New York City. She and her husband, Jason, 41, who owns a marketing company, had to make weekly trips to the hospital to have their daughter's mold adjusted.

"The mechanics of taping the device were not so tough after a little practice," Kiku says. "And after a while, she didn't mind it and sort of sucked on it as if it were a pacifier. The hardest part was when she would pull the tape off."

Although Eli Taubman's cleft did not require molding, his family was feeling plenty of anxiety the day before the surgery to repair it. "I was so upset the night before, I almost called it off," his mother says. "But just two weeks after surgery, he looked absolutely terrific. Now his lip looks like every other kid's lip."

Even so, recovery is not easy. Eli had to be fed through a syringe, and he needed arm restraints to keep him from touching his bandages. "I'm glad we went through with it," says Robin Taubman. "But I am very glad the whole thing is over."

Just a few months after her final surgery, Tani Trentlyon bears almost no sign of her severe bilateral cleft. A 15-month-old ball of energy, she smiles and babbles happily. "We've had the best results we could have imagined," says her mom. "Every day, she looks better."

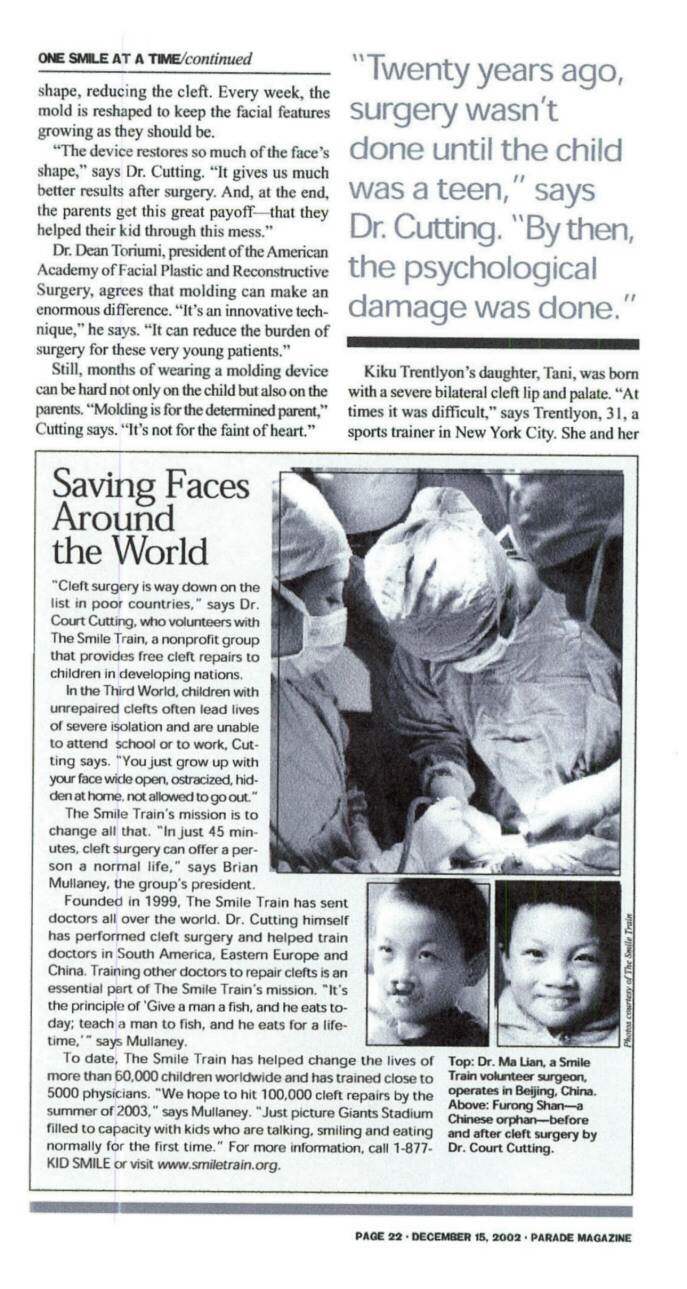

Saving Faces Around the World

"Cleft surgery is way down on the list in poor countries," says Dr. Court Cutting, who volunteers with The Smile Train, a nonprofit group that provides free cleft repairs to children in developing nations.

In the Third World, children with unrepaired clefts often lead lives of severe isolation and are unable to attend school or to work, Cutting says. "You just grow up with your face wide open, ostracized, hidden at home, not allowed to go out."

The Smile Train's mission is to change all that. "In just 45 minutes, cleft surgery can offer a person a normal life," says Brian Mullaney, the group's president.

Founded in 1999, The Smile Train has sent doctors all over the world. Dr. Cutting himself has performed cleft surgery and helped train doctors in South America, Eastern Europe and China. Training other doctors to repair clefts is an essential part of The Smile Train's mission. "It's the principle of `Give a man a fish, and he eats today; teach a man to fish, and he eats for a lifetime,'" says Mullaney.

To date, The Smile Train has helped change the lives of more than 60,000 children worldwide and has trained close to 5000 physicians. "We hope to hit 100,000 cleft repairs by the summer of 2003," says Mullaney. "Just picture Giants Stadium filled to capacity with kids who are talking, smiling and eating normally for the first time." For more information, call 1-877-KID SMILE or visit www.smiletrain.org.

For more on lip and cleft palate defects and repair, including links to resources and support groups, visit www.parade.com.

| ||||

| ||||

Clefts that

once required

several surgeries

over a number

of years to be

repaired now

can be fixed

with a single

operation

performed in

infancy.

"Twenty years ago,

surgery wasn't done

until

the child

was

a teen,"

says

Dr. Cutting.

"By then,

the

psychologocial damage

was done."

Saving Faces Around the World

A revolutionary technique to repair cleft lips and palates is changing kids' lives...

cleftAdvocate extends its thanks to all those involved in publishing this Parade Magazine article.

We subscribe to the HONcode principles of The Health On Net Foundation

This cleftAdvocate page was last updated March 25, 2014

One Smile at a Time

cleftAdvocate

a program of ameriface